2011-03-28

2011-03-27

Where the mild things are

As has been implied earlier, modelling tends to be a maledominated activity. One thinks. However, it turns out that this is mostly due to non-communicating groups: If one looks for them, one finds a huge group of female modellers and they have their own get-togethers, so today Honeybuns and I went to see the Stockholm miniature fair. The premises were crammed with middle-aged+ women hawking and buying upscale doll houses and accessories for them.

Some points that struck us:

- The vast majority of dollhouses seem to be depict some kind of Elsa Beskow world—I found only a single room with modern IKEA furniture. Oh, and a delightful Pettson & Findus house.

- There was very little in the way of tools and equipment for sale, almost everything was ready-made items. I was a bit disappointed, as I had hoped to find a good head-mounted magnifying glass.

- Was it just a coincidence that the fair was located right in the middle of upper-class Östermalm and did that have a relation to the choice of subjects? (Never mind that most of the exhibitors came from out in the countryside.)

| |

On the way home, two elderly gentlemen played baroque music on their flutes in the underground station.

Heads I win, tails you lose.

Chatting over lunch with a friend she explained how she had “premonitions” of things that would happen.

Considering she’d just had a project go down in flames, I silently wondered what the use of such premonitions would be, but instead said:

“Nah, I don’t trust in premonitions: when my aunt was in hospital, Mum said she had a premonition* she’d be OK. Two weeks later she was dead.” (I have a tendency towards rather morbid examples.)

“See! She had a premonition something would happen, she just couldn’t tell what.”

Oh, well, in that case…

* I doubt Mum had any premonitions of any sort, but just tried to cheer her sister up.

Considering she’d just had a project go down in flames, I silently wondered what the use of such premonitions would be, but instead said:

“Nah, I don’t trust in premonitions: when my aunt was in hospital, Mum said she had a premonition* she’d be OK. Two weeks later she was dead.” (I have a tendency towards rather morbid examples.)

“See! She had a premonition something would happen, she just couldn’t tell what.”

Oh, well, in that case…

* I doubt Mum had any premonitions of any sort, but just tried to cheer her sister up.

2011-03-26

Postponing judgement

Every now and then I get into discussions with, er, …persons lacking in scientific training. A common complaint, when I decline to embrace the truth of preternatural interpretations of various events, is: “Scientists think they always know everything!” Well, no.

Saying “It must have been telepathy, what else could it be?” is assuming that everything else is known and excluded.

Saying “As all well-controlled tests so far have failed to show any evidence of telepathy, it’s unlikely that that was the cause in this case either, but the amount of detail given in your anecdote only allows us to guess on alternative explanations, so we cannot really say what happened.” is tentative, wordy, and hedging, and in particular does not assume that all circumstances are known. Why is this so difficult to grasp for some?

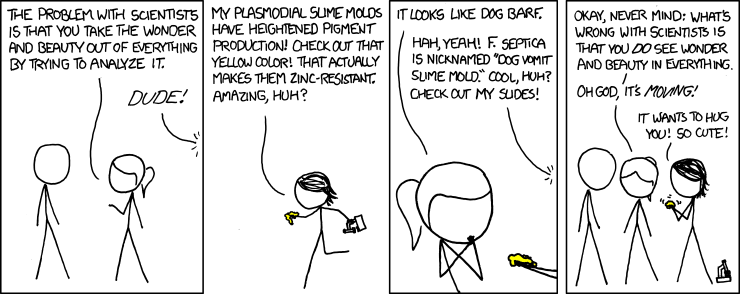

Then, Randy Munroe attacks another complaint about the dastardlyness of scientists:

(Of course all the facts about Fuligo septica are exactly as stated. Oh, and it’s called “troll butter” in Swedish.)

Saying “It must have been telepathy, what else could it be?” is assuming that everything else is known and excluded.

Saying “As all well-controlled tests so far have failed to show any evidence of telepathy, it’s unlikely that that was the cause in this case either, but the amount of detail given in your anecdote only allows us to guess on alternative explanations, so we cannot really say what happened.” is tentative, wordy, and hedging, and in particular does not assume that all circumstances are known. Why is this so difficult to grasp for some?

Then, Randy Munroe attacks another complaint about the dastardlyness of scientists:

(Of course all the facts about Fuligo septica are exactly as stated. Oh, and it’s called “troll butter” in Swedish.)

2011-03-25

Untimely

It was with a lump in my throat I found that André Gjörling has died, leaving behind a family and memories of the gentle silliness of Toffelhjältarna/Solstollarna. I find no better tribute than letting Martyna Lisowska bid him good night.

2011-03-10

Disappointed

Intrigued by a review of Model Craft’s Pick and Place tool, a handle with a sticky head with which to pick up small items (like photo-etch details and such), I tried to find one for myself. The usual hobby shops did not have them, but Panduro offered something that seems to be the identical item under the name Marvy Jewel Picker.

It did initially perform as promised, but the head lost its tackiness within days. The suggested methods of washing in warm water or rolling the head over sticky tape have not worked. I’m much disappointed in what seemed so promising.

Finished model 2011-I

The cover art on Matchbox’ “Focke-Wulf FW.190” kit has the following caption:

The painting instructions on the back of the box indicate that the aircraft on the cover comes from “111 Group J.G. 51 Fighter Unit (Eastern Front)”, i e presumably III/JG 51. More specifically, since the aircraft carries red numbers, it would be from 8./JG 51, or, spelling out the abbreviation: 8. Staffel/III Gruppe/Jagdgeschwader 51 „Mölders“. (More explanation)

Finding out more about this incident required trawling through quite a bit of references. It was known that a Günther Schack had shot down five of those Pe-2s, but what was the exact date, what unit did he belong to and what subtype of Fw 190 was he flying?

Fortunately we can go to more primary sources: the Luftwaffe claims lists give us the information we need:

And, we also find this:

So, we have one occasion of five Pe-2s shot down, and a second of four shot down. The unit definitely seems to be 7./JG 51, though it seems unlikely that Schack would have been demoted from Oberfeldwebel to Feldwebel between December and January, so some error in the sources seems to be present.

In the December incident, we see that there is a first group of four shot down within minutes (it seems likely that the first kill is also at 2500 m, rather than 250) and the last one 16 minutes later, some distance away and at a different height. When we plot this on a map we see some interesting things: III/JG51 were at the time based in Orel (marked with a red blob on the map) [Holm], and the patrol’s interception was over 200 km to the north, past Moscow. The first three kills are made while flying on a north-easterly course, but the patrol has then doubled back for the fourth. At 12:10 Unteroffizier Baumestner (presumably Schack’s wingman) shot down another Pe-2 12 km south of „Subzoff“, i e further west, and then at 12:17 Schack shot down the final Pe-2 almost at the point of the first kill. (Assuming the positions given are trustworthy and precise. Movable Type’s lat/long scripts were invaluable in fixing them on a map.) The north-easterly course would imply that the Soviet bombers were on their way home, but the question is then why the last kills were further west, as it seems unlikely that the Soviet crews would try to escape to safety in that direction, but possibly these were stragglers that had become separated from the others. That the positions are given with reference to Zubtsov rather than Sychyovka, suggests that the patrol had moved about and taken new bearings before finding the last two bombers.

The January mission was closer to home, if I have managed to convert the Jägergradnetz coordinates correctly (using LUMA). Further, the given times would indicate that the kills were made just before daybreak. Might this in fact have been an interception of a dawn raid on the airfield itself? (It is also possible that the time given was Berlin time, rather than local, Moscow, time.)

Show a bigger version.

(The map also indicates that while the landscape is not completely flat, it does not feature anything like the dramatic snow-covered mountains on the box art.)

Now, what about the aircraft? In this case the relevant document is Flugzeugbestand und Bewegungsmeldungen III./JG 51 which gives us that III/JG 51 during the relevant months had:

Clearly Schack could not have flown an A-4 at this time, but it could have been either an A-2 or an A-3. For modelling purposes they are identical, as the difference lies in the engine subtype [Baugher 2004], so we will not worry unduly about this distinction. The Matchbox kit claims to be an A-3, but in fact contains a mixture of A-3 and A-4 features, the most visible being having both the A-4’s high antenna post on the fin and the A-3’s direct lead into the fin. Well, this is pretty typical Matchbox, but onto more visible features: how would the aircraft have been painted? The painting instructions indicate a 70/71/65 camouflage, with a high demarcation line and a spinner with concentric circles in black and white, but is this supported by photographic and documentary evidence? There is relatively little in the way of photographic evidence of JG 51 Fw 190s [though see Arthy], but we can extrapolate from other Fw 190 units on the Eastern Front, primarily JG 54.

German fighters had switched from 70/71/65 to 74/75/76 camouflage in 1941, but this was dictated by high altitude flying where grey colours blended in better with the sky. On the Eastern Front, fighters were sent out against low-level bombers and attack aircraft and also needed to be better hidden on the ground, so units there reverted to the old-style camouflage. Then, when winter arrived, they were winter camouflaged with white paint over the top surfaces. However, photographs indicate that green/green aircraft were used in parallel with white-painted aircraft, there were also aircraft only partially white-painted over the green/green surfaces and then the thin layer of white would wear off fairly quickly, letting the green/green surfaces shine through.

In the end I decided, mostly out of time constraints, to go for an all-white scheme, and since they supposedly were on their first patrol, the paint would still be fresh. Weal has drawn a profile of Herbert Wehnelt’s Fw 190A-3 from 7./JG 51, though without giving any photographic source for it, that I let myself be inspired by.

Then, the markings. Clearly Matchbox’ markings were spurious (which actually is a bit surprising, usually they are based on some well-known individual), and worse, the „10“ numerals on the actual decals were for no good reason drastically simplified from the rendition on the box art, the latter which correctly depicted 8 Staffel markings in red with white surrounds. In the absence of any other evidence, I just pilfered a white number „1“ and III Gruppe vertical bar from the Kagero decal sheet nr 25 „JG 26 vol II“. Something clearly visible from available photographs was that, in opposition to JG 54, JG 51 aircraft did usually not carry any unit emblems at this time, so I didn’t have to worry about that.

Yeah, and then the actual building of the model:

I scratch-built a cockpit interior, opened up the cooling louvres behind the engine and also deepened the space behind the exhaust tubes (but didn’t bother making the tubes themselves). I wanted to build an aircraft in flight, so I filed down the tail wheel to its correct semi-retracted position. I also added an antenna cable and removed the incorrect antenna post. Some amount of filler was needed, in particular around the wings, and some panel lines needed to be (re-)scribed. Another curious item was that the wings had the bulges for MG FF cannon, but no barrels supplied. These were of course easy to add. I also created a pitot tube out of a length of syringe and a Q-tip that I stretched over a candle.

Painting was a bit of a painful process, I’m using the airbrush too seldom to become really proficient, but I think I learned some useful lessons.

Literature:

Chronik Jagdgeschwader 51 »Mölders«, Gebhard Aders & Werner Held, 2009, Motorbuch Verlag.

Aircraft Archive: Classics of World War Two, Argus Books, 1989.

“Early Focke-Wulf FW 190s on the Eastern Front: The FW 190 A-1, A-2 and A-3 with Jagdgeschwader 51”, Andrew Arthy.

“Modeller's Guide to Focke-Wulf Fw 190 Variants: Radial Engine Versions—Part I”, Joe Baugher & Martin Waligorski.

Focke Wulf FW 190 in action, Jerry L. Campbell, 1975, Squadron/Signal Publications.

Luftwaffe at War: Fighters over Russia, Manfred Griehl, 1997, Greenhill Books.

„Jagdgeschwader 51 "Mölders"“, compiled by Michael Holm.

„Flugzeugbestand und Bewegungsmeldungen: III./JG51“, compiled by Michael Holm.

“Günther Schack”, Petr Kacha.

„Schack, Günther“, Lexikon der Wehrmacht.

German Aircraft Interiors 1935–1945, vol 1, Kenneth A. Merrick, 1996, Monogram Aviation Publiations.

Focke-Wulf FW 190 im Detail, Jens Nissen, 2002, Motorbuch Verlag.

Focke-Wulf Fw 190A/F/G Luftwaffe, Christopher Shores, 1974, Osprey Publishing.

Luftwaffe Air & Ground Crew 1939–45, Robert F. Stedman, 2002, Osprey Publishing.

Oberflächenschutzverfahren und Anstrichstoffe der deutschen Luftfahrtindustrie und Luftwaffe 1935–1945, Michael Ullmann, 2000, Bernard & Graefe Verlag.

Focke-Wulf Fw 190 Aces on the Eastern Front, John Weal, 2000, Delprado Publications.

Jagdgeschwader 51 ‘Mölders’, John Weal, 2006, Osprey Publications.

“O.K.L. Fighter Claims Chef für Ausz. und Dizsiplin [sic] Luftwaffen-Personalamt L.P. (A) V Films & Supplementary Claims from Lists Eastern Front (Ostfront) August–December 1942”

“O.K.L. Fighter Claims Chef für Ausz. und Dizsiplin [sic] Luftwaffen-Personalamt L.P. (A) V Films & Supplementary Claims from Lists Eastern Front (Ostfront) January–June 1943”, compiled by Tony Wood.

Two F.W. 190’s patrolling over the Eastern Front on the 17th December 1942 are shown attacking one of the seven Petlyakov PE-2’s they destroyed on this their first sortie with the new F.W. 190.

The painting instructions on the back of the box indicate that the aircraft on the cover comes from “111 Group J.G. 51 Fighter Unit (Eastern Front)”, i e presumably III/JG 51. More specifically, since the aircraft carries red numbers, it would be from 8./JG 51, or, spelling out the abbreviation: 8. Staffel/III Gruppe/Jagdgeschwader 51 „Mölders“. (More explanation)

Finding out more about this incident required trawling through quite a bit of references. It was known that a Günther Schack had shot down five of those Pe-2s, but what was the exact date, what unit did he belong to and what subtype of Fw 190 was he flying?

- Campbell [1975] says a Lt. Gunther [sic] had shot down six Pe-2s on his first sortie with a Fw 190A-4 of III/JG 51, at some point before 1943-02-11.

- Weal [2000] says Oblt Günther Schack flew a Fw 190A-4 of 9./JG 51 and shot down five Pe-2s on 1943-01-29. This is contradicted by Weal [2006], where he says Lt Günther Schack shot down five Pe-2s on 1942-12-17 (possibly, unclear from context) while flying with a unit of III/JG 51, possibly 7./JG 51, extrapolating from the unit he’d flown with earlier in 1942.

- Shores [1974] says Lt Günther Schack shot down five Pe-2s while flying a Fw 190A-4 of III/JG 51, but gives no date.

- Kacha says Günther Schack performed this feat both on 1942-12-17 and on 1943-01-29, while flying a Fw 190A-4 of III/JG 51, possibly 7./JG 51.

- Lexikon der Wehrmacht says he flew with 7./JG 51 and was promoted Leutnant on 1943-01-01.

Fortunately we can go to more primary sources: the Luftwaffe claims lists give us the information we need:

| 17.12.42 | Ofw. Günther Schack | 7./JG 51 | Pe-2 | 25 km. N.E. Sychëvka: 250 m. (Smolensk) | 11.58 |

| 17.12.42 | Ofw. Günther Schack | 7./JG 51 | Pe-2 | 27 km. N.E. Sychëvka: 2.500 m. | 11.59 |

| 17.12.42 | Ofw. Günther Schack | 7./JG 51 | Pe-2 | 35 km. N.E. Sychëvka: 2.500 m. | 12.00 |

| 17.12.42 | Ofw. Günther Schack | 7./JG 51 | Pe-2 | 33 km. N.E. Sychëvka: 2.500 m. | 12.01 |

| 17.12.42 | Ofw. Günther Schack | 7./JG 51 | Pe-2 | 20 km. S. Subzoff: 3.000 m. | 12.17 |

And, we also find this:

| 29.01.43 | Fw. Günther Schack | 7./JG 51 | Pe-2 | 63 322: at 1.800 m. | 08.31 |

| 29.01.43 | Fw. Günther Schack | 7./JG 51 | Pe-2 | 63 444: at 1.700 m. | 08.32 |

| 29.01.43 | Fw. Günther Schack | 7./JG 51 | Pe-2 | 63 444: at 1.600 m. | 08.33 |

| 29.01.43 | Fw. Günther Schack | 7./JG 51 | Pe-2 | 63 444: at 1.500 m. | 08.34 |

So, we have one occasion of five Pe-2s shot down, and a second of four shot down. The unit definitely seems to be 7./JG 51, though it seems unlikely that Schack would have been demoted from Oberfeldwebel to Feldwebel between December and January, so some error in the sources seems to be present.

In the December incident, we see that there is a first group of four shot down within minutes (it seems likely that the first kill is also at 2500 m, rather than 250) and the last one 16 minutes later, some distance away and at a different height. When we plot this on a map we see some interesting things: III/JG51 were at the time based in Orel (marked with a red blob on the map) [Holm], and the patrol’s interception was over 200 km to the north, past Moscow. The first three kills are made while flying on a north-easterly course, but the patrol has then doubled back for the fourth. At 12:10 Unteroffizier Baumestner (presumably Schack’s wingman) shot down another Pe-2 12 km south of „Subzoff“, i e further west, and then at 12:17 Schack shot down the final Pe-2 almost at the point of the first kill. (Assuming the positions given are trustworthy and precise. Movable Type’s lat/long scripts were invaluable in fixing them on a map.) The north-easterly course would imply that the Soviet bombers were on their way home, but the question is then why the last kills were further west, as it seems unlikely that the Soviet crews would try to escape to safety in that direction, but possibly these were stragglers that had become separated from the others. That the positions are given with reference to Zubtsov rather than Sychyovka, suggests that the patrol had moved about and taken new bearings before finding the last two bombers.

The January mission was closer to home, if I have managed to convert the Jägergradnetz coordinates correctly (using LUMA). Further, the given times would indicate that the kills were made just before daybreak. Might this in fact have been an interception of a dawn raid on the airfield itself? (It is also possible that the time given was Berlin time, rather than local, Moscow, time.)

Show a bigger version.

(The map also indicates that while the landscape is not completely flat, it does not feature anything like the dramatic snow-covered mountains on the box art.)

Now, what about the aircraft? In this case the relevant document is Flugzeugbestand und Bewegungsmeldungen III./JG 51 which gives us that III/JG 51 during the relevant months had:

| 1942-11: | 7 Fw 190A-3, 6 Fw 190A-2 |

| 1942-12: | 11 Fw 190A-3, 23 Fw 190A-2 |

| 1943-01: | 16 Fw 190A-3, 16 Fw 190A-2 |

| 1943-02: | 15 Fw 190A-3, 25 Fw 190A-2 |

Clearly Schack could not have flown an A-4 at this time, but it could have been either an A-2 or an A-3. For modelling purposes they are identical, as the difference lies in the engine subtype [Baugher 2004], so we will not worry unduly about this distinction. The Matchbox kit claims to be an A-3, but in fact contains a mixture of A-3 and A-4 features, the most visible being having both the A-4’s high antenna post on the fin and the A-3’s direct lead into the fin. Well, this is pretty typical Matchbox, but onto more visible features: how would the aircraft have been painted? The painting instructions indicate a 70/71/65 camouflage, with a high demarcation line and a spinner with concentric circles in black and white, but is this supported by photographic and documentary evidence? There is relatively little in the way of photographic evidence of JG 51 Fw 190s [though see Arthy], but we can extrapolate from other Fw 190 units on the Eastern Front, primarily JG 54.

German fighters had switched from 70/71/65 to 74/75/76 camouflage in 1941, but this was dictated by high altitude flying where grey colours blended in better with the sky. On the Eastern Front, fighters were sent out against low-level bombers and attack aircraft and also needed to be better hidden on the ground, so units there reverted to the old-style camouflage. Then, when winter arrived, they were winter camouflaged with white paint over the top surfaces. However, photographs indicate that green/green aircraft were used in parallel with white-painted aircraft, there were also aircraft only partially white-painted over the green/green surfaces and then the thin layer of white would wear off fairly quickly, letting the green/green surfaces shine through.

In the end I decided, mostly out of time constraints, to go for an all-white scheme, and since they supposedly were on their first patrol, the paint would still be fresh. Weal has drawn a profile of Herbert Wehnelt’s Fw 190A-3 from 7./JG 51, though without giving any photographic source for it, that I let myself be inspired by.

Then, the markings. Clearly Matchbox’ markings were spurious (which actually is a bit surprising, usually they are based on some well-known individual), and worse, the „10“ numerals on the actual decals were for no good reason drastically simplified from the rendition on the box art, the latter which correctly depicted 8 Staffel markings in red with white surrounds. In the absence of any other evidence, I just pilfered a white number „1“ and III Gruppe vertical bar from the Kagero decal sheet nr 25 „JG 26 vol II“. Something clearly visible from available photographs was that, in opposition to JG 54, JG 51 aircraft did usually not carry any unit emblems at this time, so I didn’t have to worry about that.

Yeah, and then the actual building of the model:

I scratch-built a cockpit interior, opened up the cooling louvres behind the engine and also deepened the space behind the exhaust tubes (but didn’t bother making the tubes themselves). I wanted to build an aircraft in flight, so I filed down the tail wheel to its correct semi-retracted position. I also added an antenna cable and removed the incorrect antenna post. Some amount of filler was needed, in particular around the wings, and some panel lines needed to be (re-)scribed. Another curious item was that the wings had the bulges for MG FF cannon, but no barrels supplied. These were of course easy to add. I also created a pitot tube out of a length of syringe and a Q-tip that I stretched over a candle.

Painting was a bit of a painful process, I’m using the airbrush too seldom to become really proficient, but I think I learned some useful lessons.

Literature:

Chronik Jagdgeschwader 51 »Mölders«, Gebhard Aders & Werner Held, 2009, Motorbuch Verlag.

Aircraft Archive: Classics of World War Two, Argus Books, 1989.

“Early Focke-Wulf FW 190s on the Eastern Front: The FW 190 A-1, A-2 and A-3 with Jagdgeschwader 51”, Andrew Arthy.

“Modeller's Guide to Focke-Wulf Fw 190 Variants: Radial Engine Versions—Part I”, Joe Baugher & Martin Waligorski.

Focke Wulf FW 190 in action, Jerry L. Campbell, 1975, Squadron/Signal Publications.

Luftwaffe at War: Fighters over Russia, Manfred Griehl, 1997, Greenhill Books.

„Jagdgeschwader 51 "Mölders"“, compiled by Michael Holm.

„Flugzeugbestand und Bewegungsmeldungen: III./JG51“, compiled by Michael Holm.

“Günther Schack”, Petr Kacha.

„Schack, Günther“, Lexikon der Wehrmacht.

German Aircraft Interiors 1935–1945, vol 1, Kenneth A. Merrick, 1996, Monogram Aviation Publiations.

Focke-Wulf FW 190 im Detail, Jens Nissen, 2002, Motorbuch Verlag.

Focke-Wulf Fw 190A/F/G Luftwaffe, Christopher Shores, 1974, Osprey Publishing.

Luftwaffe Air & Ground Crew 1939–45, Robert F. Stedman, 2002, Osprey Publishing.

Oberflächenschutzverfahren und Anstrichstoffe der deutschen Luftfahrtindustrie und Luftwaffe 1935–1945, Michael Ullmann, 2000, Bernard & Graefe Verlag.

Focke-Wulf Fw 190 Aces on the Eastern Front, John Weal, 2000, Delprado Publications.

Jagdgeschwader 51 ‘Mölders’, John Weal, 2006, Osprey Publications.

“O.K.L. Fighter Claims Chef für Ausz. und Dizsiplin [sic] Luftwaffen-Personalamt L.P. (A) V Films & Supplementary Claims from Lists Eastern Front (Ostfront) August–December 1942”

“O.K.L. Fighter Claims Chef für Ausz. und Dizsiplin [sic] Luftwaffen-Personalamt L.P. (A) V Films & Supplementary Claims from Lists Eastern Front (Ostfront) January–June 1943”, compiled by Tony Wood.

2011-03-04

Coincidence? I think not!

The sister ship of HMS Tiger was HMS Blake. The Royal Navy claims it is named for Robert Blake, but I think some clever fellow at the Admiralty had William Blake in mind.

2011-03-03

Gustav III

[SPOILERS AHEAD]

It’s been altogether too long since I went to a spex, so I brought along the posse to see ”Gustav III, eller, Svårigheten att komma till skott” (“Gustav III, or, Barkeep, gimme another shot”).

It seems the state of spex has moved somewhat, at least judging from this sample, which kept high standards of acting and psychological development, while the audience had become more rowdy, constantly yelling requests at the actors. I was also a bit surprised to find that all female roles were played by actual women and the male roles all by men. (Honeybuns suggested that cross-dressing is so common it has no effect any more and thus can just be dumped.) The second-act ensemble a capella had been moved to the finale and there was no Pun Cascade worth mentioning.

That said, it was a tightly scripted exercise, starting with King Gustav away in France, shirking his duties according to his brother, the prim and stiff Duke Charles. Therefore he has hatched a plan to oust the king with the help of their cousin, Empress Catherine. Bellman, ne’er-do-well and the King’s best friend, however joyously announces that the king is returning. Hollinder, the barman at Gyldene Freden, is being henpecked by visiting nobles.

Eventually the king arrives and goes straight to Gyldene Freden to find Bellman and tell of his travels in France, where Liberty, Equality and Fraternity have just been invented. Bellman and the king celebrate their reunion with joyous horse-play, but both Duke Charles and Queen Sophia turn up to remind the king of his duties: wars and parties. Tomorrow there will be a masked ball to celebrate the return of the king and the queen wants it to be “Perfect perfect perfect”. Bellman, being a commoner, is expressly not wanted at the party. Bellman is hurt and the king is pained but forced to uphold the queen’s decree, because after all, one has to do one’s duties.

Duke Charles and Catherine have a secret meeting where he explains that the king should be made to abdicate. Catherine, a stereotypical Russian who will kiss and kill with the same hearty laugh, has no patience with such finesse and decides on her own to simply kill the king. Hollinder suggests she contact a mysterious man, known as Anckarström. This she does and hands the masked Anckarström money and a gun with which to shoot the king.

The next day the queen is dressing up the unhappy king, who vainly tries to explain that he actually does not want to be king and really not her husband either. She does not listen, but gets more and more exasperated with his uninterest in the perfect perfect perfect ball. When the king leaves, she has a chat with Catherine, who explains how she killed her husband the Czar and became ruler over the Russian empire. Sophia gets an idea. Catherine offers help—in exchange for suitable parts of the Swedish kingdom. They haggle for a while over who’ll have to take Finland. An upset Finn in the audience curses loudly.

Meanwhile the king has sought out Bellman and asks him to came to the ball anyway. Bellman has a bright idea for how the king can escape his duties and rushes off without having time to explain his idea.

Sophia finds Anckarström and hands him money and a gun with which to kill the king.

Bellman also locates Anckarström and hands him money and a gun with which to kill the king. We understand that this gun is loaded with a blank.

Before the masked ball Hollinder, who is responsible for the catering, arrives with a heavy bag, which he nervously tries to hide and then opens. It turns out to contain three guns and Anckarström’s mask and cape. He picks one of the guns at random. The ball begins.

During the ball a masked man turns up and shoots the king, who falls. Curtains.

In the final act Duke Charles is besides himself, what hath Catherine wrought, this was not his plan at all. Is the king still alive even? A physician, suspiciously similar to Bellman in disguise, assures he has the situation under control, but is also very nervous. In private with the king it turns out the king is alive, though wounded. Bellman is desperately upset that his plan backfired so badly. The king tries to console him. But, can they escape? Before they manage to leave, everybody else arrive in the king’s chamber through various secret passages. In particular a wild-eyed Hollinder arrives, determined to go into history by finishing the job with his two remaining guns. Duke Charles manages to snatch one of these for himself and there is a standoff for the space of several restarts of the ensemble a capella, and then the two men fire. Both Hollinder and the king fall. The czarina and the queen rejoice, but Duke Charles takes over the situation at swordpoint and sends them packing.

The king awakes from his faint to the joy of Bellman and the relief of Duke Charles. The king however decides it suits him to remain dead and leave for France with Bellman, leaving the kingdom in the hands of Duke Charles. The brothers solemnly take farewell and then finally Gustav and Bellman can meet in a deep kiss. The audience goes wild. Curtains.

I was quite impressed with the performance of Gustav, unwilling but duty-bound, the straight man of the play. Hollinder, also a man under pressure, got somewhat short shrift, being killed with no eulogies (though yet a better death than the real Anckarström received). On the whole an enjoyable evening.

It’s been altogether too long since I went to a spex, so I brought along the posse to see ”Gustav III, eller, Svårigheten att komma till skott” (“Gustav III, or, Barkeep, gimme another shot”).

It seems the state of spex has moved somewhat, at least judging from this sample, which kept high standards of acting and psychological development, while the audience had become more rowdy, constantly yelling requests at the actors. I was also a bit surprised to find that all female roles were played by actual women and the male roles all by men. (Honeybuns suggested that cross-dressing is so common it has no effect any more and thus can just be dumped.) The second-act ensemble a capella had been moved to the finale and there was no Pun Cascade worth mentioning.

That said, it was a tightly scripted exercise, starting with King Gustav away in France, shirking his duties according to his brother, the prim and stiff Duke Charles. Therefore he has hatched a plan to oust the king with the help of their cousin, Empress Catherine. Bellman, ne’er-do-well and the King’s best friend, however joyously announces that the king is returning. Hollinder, the barman at Gyldene Freden, is being henpecked by visiting nobles.

Eventually the king arrives and goes straight to Gyldene Freden to find Bellman and tell of his travels in France, where Liberty, Equality and Fraternity have just been invented. Bellman and the king celebrate their reunion with joyous horse-play, but both Duke Charles and Queen Sophia turn up to remind the king of his duties: wars and parties. Tomorrow there will be a masked ball to celebrate the return of the king and the queen wants it to be “Perfect perfect perfect”. Bellman, being a commoner, is expressly not wanted at the party. Bellman is hurt and the king is pained but forced to uphold the queen’s decree, because after all, one has to do one’s duties.

Duke Charles and Catherine have a secret meeting where he explains that the king should be made to abdicate. Catherine, a stereotypical Russian who will kiss and kill with the same hearty laugh, has no patience with such finesse and decides on her own to simply kill the king. Hollinder suggests she contact a mysterious man, known as Anckarström. This she does and hands the masked Anckarström money and a gun with which to shoot the king.

The next day the queen is dressing up the unhappy king, who vainly tries to explain that he actually does not want to be king and really not her husband either. She does not listen, but gets more and more exasperated with his uninterest in the perfect perfect perfect ball. When the king leaves, she has a chat with Catherine, who explains how she killed her husband the Czar and became ruler over the Russian empire. Sophia gets an idea. Catherine offers help—in exchange for suitable parts of the Swedish kingdom. They haggle for a while over who’ll have to take Finland. An upset Finn in the audience curses loudly.

Meanwhile the king has sought out Bellman and asks him to came to the ball anyway. Bellman has a bright idea for how the king can escape his duties and rushes off without having time to explain his idea.

Sophia finds Anckarström and hands him money and a gun with which to kill the king.

Bellman also locates Anckarström and hands him money and a gun with which to kill the king. We understand that this gun is loaded with a blank.

Before the masked ball Hollinder, who is responsible for the catering, arrives with a heavy bag, which he nervously tries to hide and then opens. It turns out to contain three guns and Anckarström’s mask and cape. He picks one of the guns at random. The ball begins.

During the ball a masked man turns up and shoots the king, who falls. Curtains.

In the final act Duke Charles is besides himself, what hath Catherine wrought, this was not his plan at all. Is the king still alive even? A physician, suspiciously similar to Bellman in disguise, assures he has the situation under control, but is also very nervous. In private with the king it turns out the king is alive, though wounded. Bellman is desperately upset that his plan backfired so badly. The king tries to console him. But, can they escape? Before they manage to leave, everybody else arrive in the king’s chamber through various secret passages. In particular a wild-eyed Hollinder arrives, determined to go into history by finishing the job with his two remaining guns. Duke Charles manages to snatch one of these for himself and there is a standoff for the space of several restarts of the ensemble a capella, and then the two men fire. Both Hollinder and the king fall. The czarina and the queen rejoice, but Duke Charles takes over the situation at swordpoint and sends them packing.

The king awakes from his faint to the joy of Bellman and the relief of Duke Charles. The king however decides it suits him to remain dead and leave for France with Bellman, leaving the kingdom in the hands of Duke Charles. The brothers solemnly take farewell and then finally Gustav and Bellman can meet in a deep kiss. The audience goes wild. Curtains.

I was quite impressed with the performance of Gustav, unwilling but duty-bound, the straight man of the play. Hollinder, also a man under pressure, got somewhat short shrift, being killed with no eulogies (though yet a better death than the real Anckarström received). On the whole an enjoyable evening.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)